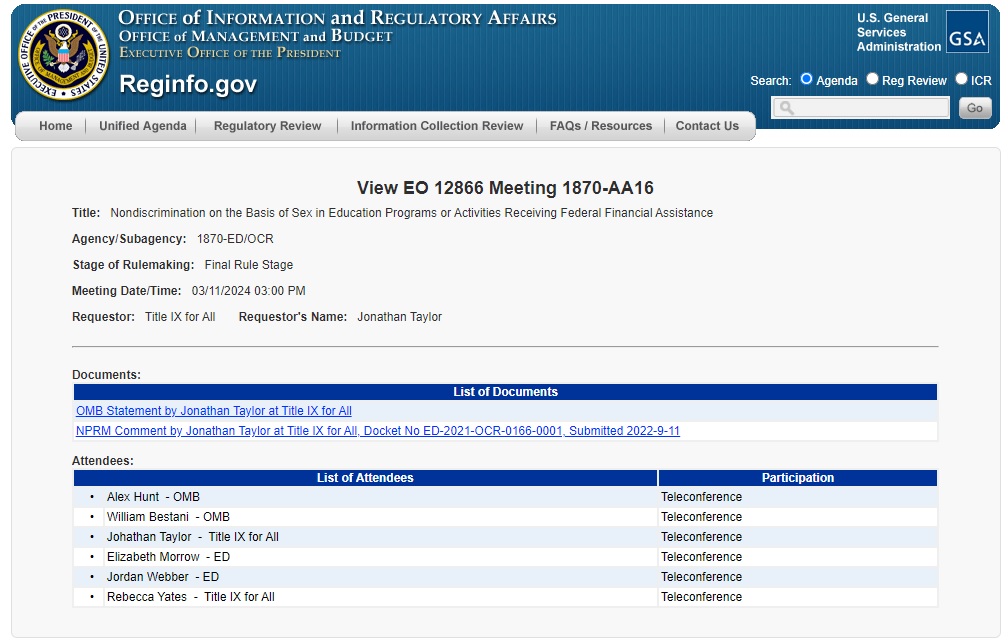

On Tuesday, March 11th, I attended a teleconference with the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) to talk for just over twenty minutes about the new Title IX regulations. As you can see in the screenshot from the OMB website, five people attended the call: two from OMB and three from the Department of Education (Rebecca Yates is an attorney at the Department of Education but is erroneously listed on the OMB website as a member of Title IX for All).

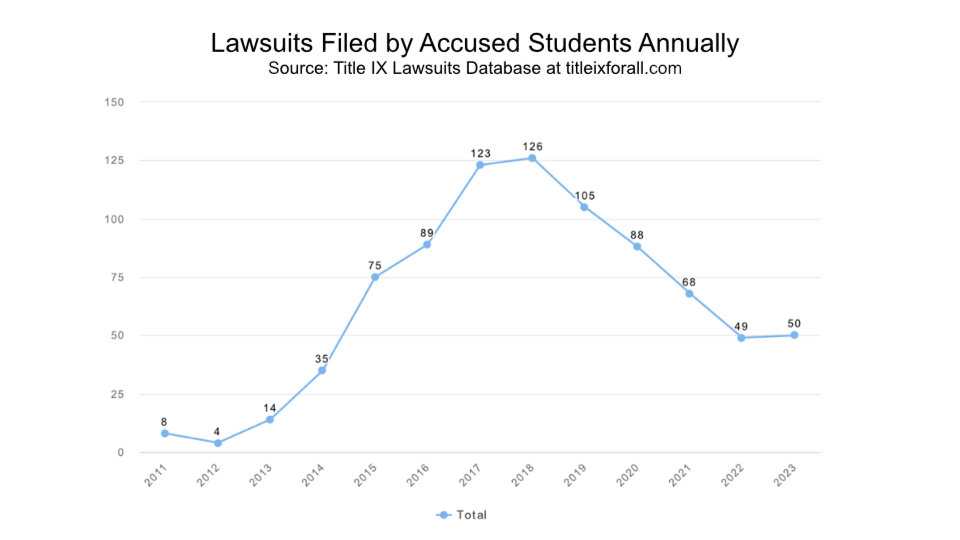

Overall, the call felt like it went better than expected when it was over, and it felt like they gave me a fair hearing. They were particularly receptive to my discussion on the graph below, how it correlates with the emphasis (or lack thereof) on due process by the administration, the balance of rights between complainants and respondents, and the resources that institutions must spend on litigation.

I made a few other arguments (some of which are listed here), but they generated less engagement. They asked some good questions, such as:

1. If there was an underreporting problem. My answer: yes, but underreporting needs to be defined better: in particular, when victims want to report but face barriers to reporting that institutions can remedy.

2. If the history of lawsuits by accused students is enough for universities to treat respondents fairly, even if the proposed regulations went into effect. My answer was no; while it may curb some of the worst abuses, it would if anything legitimize and provide cover for many others, and universities will continue to act in their interests first and foremost.

3. What can be done to improve underreporting that the current or proposed regs do not require. This was an interesting question because it seemed to stray outside the scope of the regs being discussed, but it did show what their concerns were as well as what concerns were likely (and predictably) consistently raised by advocates for complainants. Schools have done much over the past twenty years to improve underreporting, including sketchy systems like fully anonymous reporting. But one thing that schools tend to not do well is sufficiently inform complainants/victims that there are tradeoffs to how, when, and whether they report.

This is at odds with what is often argued: that there is “no wrong way” for victims to report/respond to their victimization. Of course, this can set victims up to fail when critical evidence evaporates with the passage of time because they delayed reporting…because they were told there is “no wrong way” to report/respond.

Actual and potential victims do need to be told that there are tradeoffs to delayed reporting, including evidence evaporating with the passage of time, among other concerns. They need to be told that depending on what your goals are – whether to move on with your life, hold a perpetrator accountable, or establish boundaries and seek protections to feel safe, there are ways to respond that will contribute to or work against that goal.

By the time I met with OMB they had already met with advocates for complainants. This allowed me to tease out and respond to what I suspected their arguments were, in particular: that advocates have been arguing (unpersuasively, because the argument is never attended by data, credible or otherwise) that there has been a sharp drop in reporting by victims because of the due process provisions of the 2020 regulations.

OMB confirmed as much: that they have not brought any data to show the issue was systemic per se, only anecdotes. I further added that if there truly had been a sharp increase in schools treating complainants unfairly, we would likely see evidence of that in the form of a large increase in their filing federal lawsuits, but that has not occurred.

Lastly, they asked me if I had any questions for them. While I had spoken briefly about the financial impact of the new regulations, I asked them if I had not gone far enough in addressing that issue. I further asked if they preferred to primarily address that as opposed to primarily matters of law and fairness or even giving them equal time. Their answer was that they consider “both extensively” and are interested in hearing from the public on both.

Thank You for Reading

If you like what you have read, feel free to sign up for our newsletter here:

About the Author

Related Posts

On Tuesday, March 11th, I attended a teleconference with the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) to talk for just over twenty minutes about the new Title IX regulations. As you can see in the screenshot from the OMB website, five people attended the call: two from OMB and three from the Department of Education (Rebecca Yates is an attorney at the Department of Education but is erroneously listed on the OMB website as a member of Title IX for All).

Overall, the call felt like it went better than expected when it was over, and it felt like they gave me a fair hearing. They were particularly receptive to my discussion on the graph below, how it correlates with the emphasis (or lack thereof) on due process by the administration, the balance of rights between complainants and respondents, and the resources that institutions must spend on litigation.

I made a few other arguments (some of which are listed here), but they generated less engagement. They asked some good questions, such as:

1. If there was an underreporting problem. My answer: yes, but underreporting needs to be defined better: in particular, when victims want to report but face barriers to reporting that institutions can remedy.

2. If the history of lawsuits by accused students is enough for universities to treat respondents fairly, even if the proposed regulations went into effect. My answer was no; while it may curb some of the worst abuses, it would if anything legitimize and provide cover for many others, and universities will continue to act in their interests first and foremost.

3. What can be done to improve underreporting that the current or proposed regs do not require. This was an interesting question because it seemed to stray outside the scope of the regs being discussed, but it did show what their concerns were as well as what concerns were likely (and predictably) consistently raised by advocates for complainants. Schools have done much over the past twenty years to improve underreporting, including sketchy systems like fully anonymous reporting. But one thing that schools tend to not do well is sufficiently inform complainants/victims that there are tradeoffs to how, when, and whether they report.

This is at odds with what is often argued: that there is “no wrong way” for victims to report/respond to their victimization. Of course, this can set victims up to fail when critical evidence evaporates with the passage of time because they delayed reporting…because they were told there is “no wrong way” to report/respond.

Actual and potential victims do need to be told that there are tradeoffs to delayed reporting, including evidence evaporating with the passage of time, among other concerns. They need to be told that depending on what your goals are – whether to move on with your life, hold a perpetrator accountable, or establish boundaries and seek protections to feel safe, there are ways to respond that will contribute to or work against that goal.

By the time I met with OMB they had already met with advocates for complainants. This allowed me to tease out and respond to what I suspected their arguments were, in particular: that advocates have been arguing (unpersuasively, because the argument is never attended by data, credible or otherwise) that there has been a sharp drop in reporting by victims because of the due process provisions of the 2020 regulations.

OMB confirmed as much: that they have not brought any data to show the issue was systemic per se, only anecdotes. I further added that if there truly had been a sharp increase in schools treating complainants unfairly, we would likely see evidence of that in the form of a large increase in their filing federal lawsuits, but that has not occurred.

Lastly, they asked me if I had any questions for them. While I had spoken briefly about the financial impact of the new regulations, I asked them if I had not gone far enough in addressing that issue. I further asked if they preferred to primarily address that as opposed to primarily matters of law and fairness or even giving them equal time. Their answer was that they consider “both extensively” and are interested in hearing from the public on both.

Thank You for Reading

If you like what you have read, feel free to sign up for our newsletter here:

About the Author

Related Posts

More from Title IX for All

Accused Students Database

Research due process and similar lawsuits by students accused of Title IX violations (sexual assault, harassment, dating violence, stalking, etc.) in higher education.

OCR Resolutions Database

Research resolved Title IX investigations of K-12 and postsecondary institutions by the Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights (OCR).

Attorneys Directory

A basic directory for looking up Title IX attorneys, most of whom have represented parties in litigation by accused students.