A recent article out of the NBC affiliate WILX 10 tells us:

Missing from this Advanced Placement English class at Williamston High School are the boys. Just three in Jean Eddington-Shipman’s class this semester. “When I first started teaching AP 27 years ago, it was a much better balance,” Eddington-Shipman said.

Not anymore. Girls are very consistently at the head of the class. Last year, 80 percent of the top graduates from East Lansing, Everett, Mason, Owosso, and Sexton high schools were girls, according to the Great Grads published in the Lansing State Journal. At Williamston High School, it was two-thirds.

“I’ve never had a graduating class where there were more boys that were top graduates than girls,” said Williamston Principal Jeffrey Thoenes, who’s spent nine years as a high school principal both in mid-Michigan and in Mt. Pleasant.

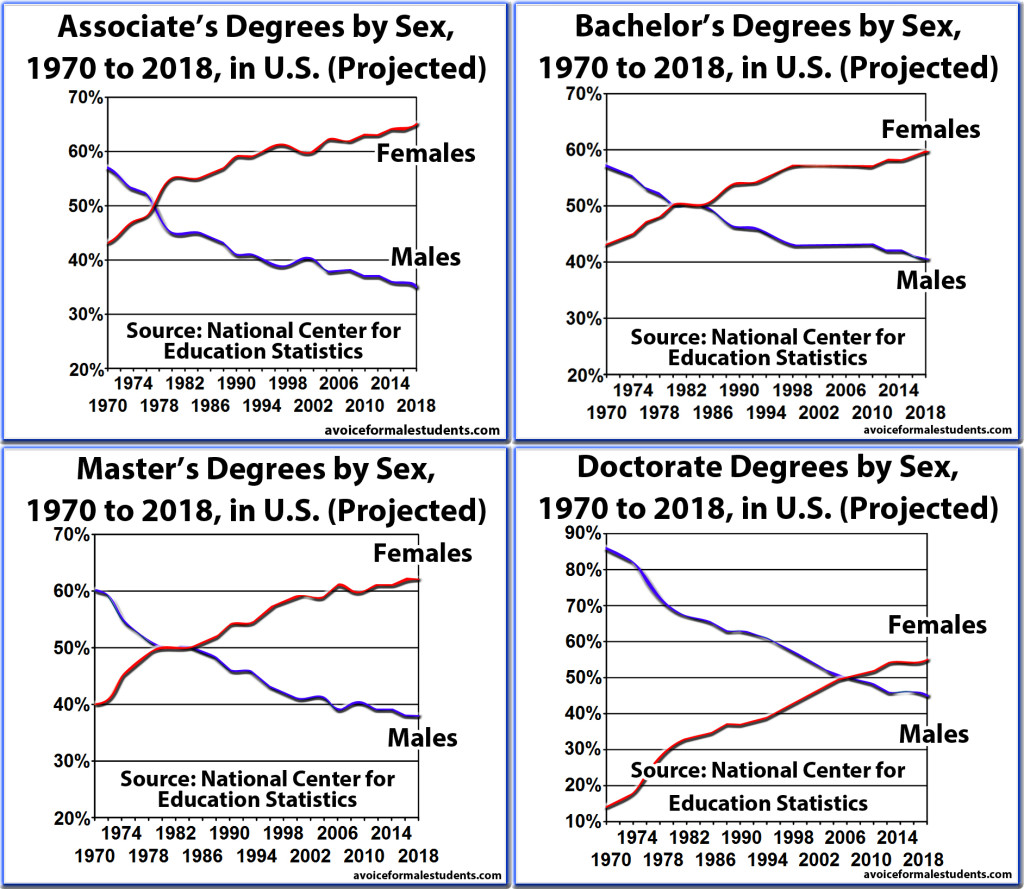

It is unfortunate that boys have fallen so far behind at Williamston High School. It is also unsurprising to anyone who has studied these issues and understands that this is not a localized phenomenon, but part of a national trend. And these disparities in aptitude don’t end with high school; they also manifest themselves starkly in higher education where male students are much less likely to earn degrees in virtually every category. As you can see below in the data from the National Center for Education Statistics:

The greatest trouble boys have is in literacy skills – reading, and especially writing. As Thomas Newkirk reports in his highly recommended book Misreading Masculinity, the Educational Testing Services (ETS) has measured that the gap favoring girls in writing concepts is now six times greater than the gap favoring boys in math concepts [1].

Boys are also 75% of students diagnosed with learning disabilities, 66% more likely to drop out of high school, four times as likely to commit suicide, twice as likely to be suspended, and three times as likely to be expelled. And more (click here for a collection of these data with a list of sources).

You might think all of these disparities, when put together, might mean something. Especially to those who style themselves as experts on educational equity and who we pay very comfortable salaries to monitor these gaps and propose solutions on how to close them.

Unfortunately, you would be mistaken.

Dr. Muhammad Khalifa is an assistant professor in the Department of Educational Administration at Michigan State University. According to his profile, his areas of expertise are “diverse learners and educational equity.” When interviewed by WILX 10, he says “There’s no evidence that I’m aware of at all that suggests boys are doing worse. It’s that girls are doing better.”

It would be one thing if Dr. Khalifa acknowledged boys’ education issues but debated the extent that they could be characterized as a crisis. But that’s not what he’s doing here. He’s flat-out saying there’s no data to suggest boys are doing worse. All I can say is this:

Really? Given the data above, one might wonder at what point the decline in male educational achievement and well-being does become an issue. Would it perhaps be an issue when boys are 95% of those diagnosed with learning disabilities? Or perhaps when male students are only 10% of those who graduate from college? Perhaps when boys are 95% of those suspended and expelled?

“But ah,” some may say, “he didn’t say ‘there’s no data that suggests boys are doing worse.’ He said ‘there’s no data I’m aware of.'”

Quite right. But consider why this expert isn’t aware of any such data in the first place – assuming he’s telling the truth, of course. This isn’t some kind of secret information that is tucked away in a file cabinet somewhere, password-protected, and stamped with a label of “classified.” These data are widely available to the general public. The methods of looking them up aren’t brain surgery or rocket science; they can all be found via a simple Google search.

Furthermore, educational equity is his self-stated area of expertise, and knowledge of such data is a basic tool of the job. It’s his job to know. Is it reasonable that a professional whose job it is to monitor the gaps in educational attainment would be unaware of it? As Supreme Court Justice Scalia said in Maryland v. King, such an idea “taxes the credulity of the credulous.”

So we are then left to question: is Dr. Khalifa “unaware” of such issues because he does not know? As the article continues he tips his hand:

Khalifa points out we live in a male-dominated society, and that women are still under-represented in science, technology, engineering and math fields. “Boys are outperforming girls and being out-paid, are landing more jobs, are being promoted, are heading industries in the STEM fields, far more than girls,” Khalifa said.

“Just because two groups are being compared to each other and one group starts to outperform another in some area, that doesn’t necessarily mean that this group is all of a sudden in danger or something like that,” he explained. “In fact, if you look at the societal context, they’re not.”

Let’s talk about that societal context a little bit more. It is true that if you look at the top of society you will find far more men than women. And that is exactly what we have been doing – indeed, all that we have been doing when it comes to discussing gender equity in education – for decades.

Now here’s an alternative perspective: look down at the bottom of society for a change. Instead of only asking which sex has the best jobs, let’s also ask: which sex is overrepresented among the most brutal, filthy, and dangerous jobs, and is consequently 93% of those who die at work? Which sex is the vast majority of those living on the street? Which sex is 93% of those in prison?

The answer? It’s men and boys, and disproportionately men and boys of color (see here for a list of men’s issues with sources). While men are indeed overrepresented at the top of society, they are also overrepresented at the bottom as well, whereas women tend to be bunched in the middle. And that truly is looking at gender issues in an expanded and inclusive societal context.

If someone employed in higher education walked around saying “I’ll care about women’s issues in education whenever men are no longer 85% of the homeless and 93% of those who die on the job,” such a person would be instantly labeled persona non grata by their peers. If they were employed in a diversity position and used such a rationale to refuse to comply with Title IX regulations and guidelines, that person would be fired from their job.

But when such attitudes are expressed toward men and boys, there is no outcry. The higher ed community regards it as entirely unremarkable. Why? Because when it comes to those who currently dominate the discourse on gender equity and diversity, such attitudes are the norm.

There are some other holes in Dr. Khalifa’s arguments. Yes, even though far more women than men graduate overall, significantly more men than women are graduating with STEM degrees and getting related jobs [EDITOR’S NOTE: it has later been discovered that this is not really the case. See here.]. But does that encapsulate their educational experience holistically? For example, if a young man can write code proficiently but can’t get a passing grade on a research paper without a teacher throwing him a curve by the time he graduates with a bachelor’s, has he acquired a well-rounded education? Is he sufficiently educated if he has the technical skills to develop software, but doesn’t have the verbal skills to market himself successfully?

I don’t think so.

Now if you were underinformed about boys’ education issues, this next one would slip past you. Admittedly, it slips past a lot of people:

Boys are still excelling on standardized testing. For example, Okemos High School has seven male students who are National Merit Semi-Finalists this year, compared to two female students. The National Merit Scholarship Program is based on PSAT scores. So far this school year, Okemos has had one student earn a perfect 36 on the ACT: a male student.

I know better than to accept this kind of framing. When you are being told that boys score better on SATs and ACTs and that alone should warrant dismissal of boys’ education issues, beware: you aren’t being told everything. As Dr. Janet Hyde of the University of Wisconsin points out:

In 2007 the SAT was taken by 798,030 females but only 690,500 males, a gap of more than 100,000 people. Assuming that SAT takers represent the top portion of the performance distribution, this surplus of females taking the SAT means that the female group dips farther down into the performance distribution than does the male group.

It is therefore not surprising that females, on average, score somewhat lower than males. The gender gap is likely in large part a sampling artifact.

In other words, 86% as many males as females took the SAT exam. Mark Perry, writing for the Encyclopedia Brittanica blog, summarized these implications quite nicely:

In other words, it is only because more females than males take the SAT exam that males score higher on average than females, and if the sample sizes were more equal, the difference in mean math test scores would disappear…if the number of females taking the math SAT exam relative to males (and female percentage of total) increases over time, the male-female math test score gap should INCREASE over time, since an increasing number of females (and increasing percent of total) taking the SAT should lower female mean math test scores over time relative to male math test scores.

Reason? The increasing number of females taking the SAT will “dip further down into the performance distribution” over time.

Just because a few males earn the highest grades in a particular metric doesn’t mean males in general are doing great. Consider this hypothetical scenario: if one male student takes a gateway exam and earns a perfect score while ten thousand female students take the same exam and earn a near-perfect score, does that mean more males than females are successful in education?

No. Granted, the above argument is an exaggeration to drive home the point. But no. You have to factor in not only who takes the test, but also who doesn’t because they aren’t prepared for it. And those who don’t take the test will not be able to qualify for scholarships and admissions in higher education nearly as well as those who do. And the same rationale holds for those who take the ACTs as well.

Notes:

[1] Educational Testing Services (ETS) Gender Study, “Trends by Subject, Fourth through Twelfth Grades,” Figure 2-1. Cited in Misreading Masculinity by Thomas Newkirk, p. 35. [2] Why Boys Fail by Richard Whitmire, p.23Thank You for Reading

If you like what you have read, feel free to sign up for our newsletter here:

About the Author

Related Posts

7 Comments

Comments are closed.

A recent article out of the NBC affiliate WILX 10 tells us:

Missing from this Advanced Placement English class at Williamston High School are the boys. Just three in Jean Eddington-Shipman’s class this semester. “When I first started teaching AP 27 years ago, it was a much better balance,” Eddington-Shipman said.

Not anymore. Girls are very consistently at the head of the class. Last year, 80 percent of the top graduates from East Lansing, Everett, Mason, Owosso, and Sexton high schools were girls, according to the Great Grads published in the Lansing State Journal. At Williamston High School, it was two-thirds.

“I’ve never had a graduating class where there were more boys that were top graduates than girls,” said Williamston Principal Jeffrey Thoenes, who’s spent nine years as a high school principal both in mid-Michigan and in Mt. Pleasant.

It is unfortunate that boys have fallen so far behind at Williamston High School. It is also unsurprising to anyone who has studied these issues and understands that this is not a localized phenomenon, but part of a national trend. And these disparities in aptitude don’t end with high school; they also manifest themselves starkly in higher education where male students are much less likely to earn degrees in virtually every category. As you can see below in the data from the National Center for Education Statistics:

The greatest trouble boys have is in literacy skills – reading, and especially writing. As Thomas Newkirk reports in his highly recommended book Misreading Masculinity, the Educational Testing Services (ETS) has measured that the gap favoring girls in writing concepts is now six times greater than the gap favoring boys in math concepts [1].

Boys are also 75% of students diagnosed with learning disabilities, 66% more likely to drop out of high school, four times as likely to commit suicide, twice as likely to be suspended, and three times as likely to be expelled. And more (click here for a collection of these data with a list of sources).

You might think all of these disparities, when put together, might mean something. Especially to those who style themselves as experts on educational equity and who we pay very comfortable salaries to monitor these gaps and propose solutions on how to close them.

Unfortunately, you would be mistaken.

Dr. Muhammad Khalifa is an assistant professor in the Department of Educational Administration at Michigan State University. According to his profile, his areas of expertise are “diverse learners and educational equity.” When interviewed by WILX 10, he says “There’s no evidence that I’m aware of at all that suggests boys are doing worse. It’s that girls are doing better.”

It would be one thing if Dr. Khalifa acknowledged boys’ education issues but debated the extent that they could be characterized as a crisis. But that’s not what he’s doing here. He’s flat-out saying there’s no data to suggest boys are doing worse. All I can say is this:

Really? Given the data above, one might wonder at what point the decline in male educational achievement and well-being does become an issue. Would it perhaps be an issue when boys are 95% of those diagnosed with learning disabilities? Or perhaps when male students are only 10% of those who graduate from college? Perhaps when boys are 95% of those suspended and expelled?

“But ah,” some may say, “he didn’t say ‘there’s no data that suggests boys are doing worse.’ He said ‘there’s no data I’m aware of.'”

Quite right. But consider why this expert isn’t aware of any such data in the first place – assuming he’s telling the truth, of course. This isn’t some kind of secret information that is tucked away in a file cabinet somewhere, password-protected, and stamped with a label of “classified.” These data are widely available to the general public. The methods of looking them up aren’t brain surgery or rocket science; they can all be found via a simple Google search.

Furthermore, educational equity is his self-stated area of expertise, and knowledge of such data is a basic tool of the job. It’s his job to know. Is it reasonable that a professional whose job it is to monitor the gaps in educational attainment would be unaware of it? As Supreme Court Justice Scalia said in Maryland v. King, such an idea “taxes the credulity of the credulous.”

So we are then left to question: is Dr. Khalifa “unaware” of such issues because he does not know? As the article continues he tips his hand:

Khalifa points out we live in a male-dominated society, and that women are still under-represented in science, technology, engineering and math fields. “Boys are outperforming girls and being out-paid, are landing more jobs, are being promoted, are heading industries in the STEM fields, far more than girls,” Khalifa said.

“Just because two groups are being compared to each other and one group starts to outperform another in some area, that doesn’t necessarily mean that this group is all of a sudden in danger or something like that,” he explained. “In fact, if you look at the societal context, they’re not.”

Let’s talk about that societal context a little bit more. It is true that if you look at the top of society you will find far more men than women. And that is exactly what we have been doing – indeed, all that we have been doing when it comes to discussing gender equity in education – for decades.

Now here’s an alternative perspective: look down at the bottom of society for a change. Instead of only asking which sex has the best jobs, let’s also ask: which sex is overrepresented among the most brutal, filthy, and dangerous jobs, and is consequently 93% of those who die at work? Which sex is the vast majority of those living on the street? Which sex is 93% of those in prison?

The answer? It’s men and boys, and disproportionately men and boys of color (see here for a list of men’s issues with sources). While men are indeed overrepresented at the top of society, they are also overrepresented at the bottom as well, whereas women tend to be bunched in the middle. And that truly is looking at gender issues in an expanded and inclusive societal context.

If someone employed in higher education walked around saying “I’ll care about women’s issues in education whenever men are no longer 85% of the homeless and 93% of those who die on the job,” such a person would be instantly labeled persona non grata by their peers. If they were employed in a diversity position and used such a rationale to refuse to comply with Title IX regulations and guidelines, that person would be fired from their job.

But when such attitudes are expressed toward men and boys, there is no outcry. The higher ed community regards it as entirely unremarkable. Why? Because when it comes to those who currently dominate the discourse on gender equity and diversity, such attitudes are the norm.

There are some other holes in Dr. Khalifa’s arguments. Yes, even though far more women than men graduate overall, significantly more men than women are graduating with STEM degrees and getting related jobs [EDITOR’S NOTE: it has later been discovered that this is not really the case. See here.]. But does that encapsulate their educational experience holistically? For example, if a young man can write code proficiently but can’t get a passing grade on a research paper without a teacher throwing him a curve by the time he graduates with a bachelor’s, has he acquired a well-rounded education? Is he sufficiently educated if he has the technical skills to develop software, but doesn’t have the verbal skills to market himself successfully?

I don’t think so.

Now if you were underinformed about boys’ education issues, this next one would slip past you. Admittedly, it slips past a lot of people:

Boys are still excelling on standardized testing. For example, Okemos High School has seven male students who are National Merit Semi-Finalists this year, compared to two female students. The National Merit Scholarship Program is based on PSAT scores. So far this school year, Okemos has had one student earn a perfect 36 on the ACT: a male student.

I know better than to accept this kind of framing. When you are being told that boys score better on SATs and ACTs and that alone should warrant dismissal of boys’ education issues, beware: you aren’t being told everything. As Dr. Janet Hyde of the University of Wisconsin points out:

In 2007 the SAT was taken by 798,030 females but only 690,500 males, a gap of more than 100,000 people. Assuming that SAT takers represent the top portion of the performance distribution, this surplus of females taking the SAT means that the female group dips farther down into the performance distribution than does the male group.

It is therefore not surprising that females, on average, score somewhat lower than males. The gender gap is likely in large part a sampling artifact.

In other words, 86% as many males as females took the SAT exam. Mark Perry, writing for the Encyclopedia Brittanica blog, summarized these implications quite nicely:

In other words, it is only because more females than males take the SAT exam that males score higher on average than females, and if the sample sizes were more equal, the difference in mean math test scores would disappear…if the number of females taking the math SAT exam relative to males (and female percentage of total) increases over time, the male-female math test score gap should INCREASE over time, since an increasing number of females (and increasing percent of total) taking the SAT should lower female mean math test scores over time relative to male math test scores.

Reason? The increasing number of females taking the SAT will “dip further down into the performance distribution” over time.

Just because a few males earn the highest grades in a particular metric doesn’t mean males in general are doing great. Consider this hypothetical scenario: if one male student takes a gateway exam and earns a perfect score while ten thousand female students take the same exam and earn a near-perfect score, does that mean more males than females are successful in education?

No. Granted, the above argument is an exaggeration to drive home the point. But no. You have to factor in not only who takes the test, but also who doesn’t because they aren’t prepared for it. And those who don’t take the test will not be able to qualify for scholarships and admissions in higher education nearly as well as those who do. And the same rationale holds for those who take the ACTs as well.

Notes:

[1] Educational Testing Services (ETS) Gender Study, “Trends by Subject, Fourth through Twelfth Grades,” Figure 2-1. Cited in Misreading Masculinity by Thomas Newkirk, p. 35. [2] Why Boys Fail by Richard Whitmire, p.23Thank You for Reading

If you like what you have read, feel free to sign up for our newsletter here:

About the Author

Related Posts

7 Comments

-

Excellent article. Brought to the attention of AVFM staff.

-

Excellent job Johnathan,

The part detailing statistical bias in standardized test scores being trotted out as evidence of boys doing just fine is enlightening. I learn something new with each one of your articles.

Keep up the good work and thank you for all you are doing here.

-

Excellent article. I don’t know whether you are familiar with this recent research or not but there are two articles that show that female (but not male) teachers give lower grades to boys (than to girls) for the same performance. It’s based on the US and the UK data. One is called: “Students’ Perceptions of Teacher Biases:

Experimental Economics in Schools” by Ouazad and Page, available at http://ssrn.com/abstract=1782675

And another “Non-cognitive Skills and the Gender Disparities in Test Scores and Teacher Assessments: Evidence from Primary School” by Cornwell and Mustard. The former is 2011 and the latter is 2012.We all know who are the majority of teachers in school.

-

Jonathan,

I pushed send before I intended. Below is the revised posting:

I appreciate this blog entry, and find much resonance in what you are saying here! My interview with WILX lasted for nearly an hour, and some of the same points you raise here, I also raised in the interview. But of course, that is not easily conveyed or captured in a 3-minute snipit on the evening news! As you know, when a broader point is being made, a few sentences here or there cannot really do justice.

Let me take this moment to clear up a few of the misunderstandings that you appear to be having about what I intended to convey, and perhaps about the topic in general of the gender gap. One, I hoped to convey that while there is some evidence that boys are doing worse than girls, the data is far more mixed and nuanced than broad, generalized statements about this problem. And, depending on which data you look at, the gap is a lot more mixed than what you may think. I will include a few scholarly references for you, and if you do not have access to them, just email me, and I will email you back the articles as soon as I can. Here are a few of the more recent articles, but there are many, many more similar references:

http://aer.sagepub.com/content/48/2/268.short

http://dericbownds.net/uploaded_images/hyde.pdf

http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/09540259920500#.UrYuw2RDunUAs the articles indicate–and again, this is not to say issues do not exist– the problem is far more complex than what you seem to be indicating here on your blog. Now, I have no problems with the second and third points you make, namely:

“that boys’ behavioral problems can at times be the result and symptoms of prior academic problems, rather than the other way around”

and:

“that the rules in lower education are created and enforced fairly and equitably.”

Regarding the first point, that was not an assumption of mine, but, it is far more complex than what is being led on here. There is quite a bit of research that suggests that (and for lack of a widely used term, I’ll say ‘boy behaviors’) “boy behaviors” are routinely targeted and heavily scrutinized in school. This point, which I stated in the interview but it didn’t make it out as clear, can help explain why boys feel uncomfortable, targeted, and may eventually leave school because of such hostile school cultures. And finally, to your third point, anyone familiar with my research could not possibly take away that I felt school rules are enforced fairly and equitably. In fact, I argue just opposite in most of my published research! More specifically, I demonstrate that the rules are unfairly and deleteriously applied to some groups, in particularly Black and Latino *males.* And that this deeply negatively impacts their school success.

Finally, the graphs you referenced, which may indeed seem problematic, is, one, referring to higher education and not K-12, which was what the interview was primarily about, and two, could be more useful if it was pulled out by subject area. It is a problem that men are not entering some fields–I agree! But there is no doubt at all that men still predominate some of the highest paying professional fields, top management positions, and that equally-qualified women make a portion of what men make. That is one of the major points I hoped to convey in the interview. More broadly speaking, it would really help you to reference some of the scholarly literature about oppression and marginalization in school and society, and that would only help you more cogently make many of the points you hope to make. But it would also help you better understand the plight of women a bit better. So to sum it all up, while I agree there are some issues with boys in school, it is not nearly as one-sided and dire as you seem to be suggesting.

Nonetheless, I am glad we had a chance for this exchange, and I encourage more exchanges like this. For any readers wanting more comprehensive research on the gender gap, feel free to email me and I will send along whatever I can. Best wishes!

-Dr. Muhammad Khalifa

Comments are closed.

More from Title IX for All

Accused Students Database

Research due process and similar lawsuits by students accused of Title IX violations (sexual assault, harassment, dating violence, stalking, etc.) in higher education.

OCR Resolutions Database

Research resolved Title IX investigations of K-12 and postsecondary institutions by the Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights (OCR).

Excellent article. Brought to the attention of AVFM staff.

Awesome. Glad you like it.

Excellent job Johnathan,

The part detailing statistical bias in standardized test scores being trotted out as evidence of boys doing just fine is enlightening. I learn something new with each one of your articles.

Keep up the good work and thank you for all you are doing here.

Thank you. Will do :)

Excellent article. I don’t know whether you are familiar with this recent research or not but there are two articles that show that female (but not male) teachers give lower grades to boys (than to girls) for the same performance. It’s based on the US and the UK data. One is called: “Students’ Perceptions of Teacher Biases:

Experimental Economics in Schools” by Ouazad and Page, available at http://ssrn.com/abstract=1782675

And another “Non-cognitive Skills and the Gender Disparities in Test Scores and Teacher Assessments: Evidence from Primary School” by Cornwell and Mustard. The former is 2011 and the latter is 2012.

We all know who are the majority of teachers in school.

Jonathan,

I pushed send before I intended. Below is the revised posting:

I appreciate this blog entry, and find much resonance in what you are saying here! My interview with WILX lasted for nearly an hour, and some of the same points you raise here, I also raised in the interview. But of course, that is not easily conveyed or captured in a 3-minute snipit on the evening news! As you know, when a broader point is being made, a few sentences here or there cannot really do justice.

Let me take this moment to clear up a few of the misunderstandings that you appear to be having about what I intended to convey, and perhaps about the topic in general of the gender gap. One, I hoped to convey that while there is some evidence that boys are doing worse than girls, the data is far more mixed and nuanced than broad, generalized statements about this problem. And, depending on which data you look at, the gap is a lot more mixed than what you may think. I will include a few scholarly references for you, and if you do not have access to them, just email me, and I will email you back the articles as soon as I can. Here are a few of the more recent articles, but there are many, many more similar references:

http://aer.sagepub.com/content/48/2/268.short

http://dericbownds.net/uploaded_images/hyde.pdf

http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/09540259920500#.UrYuw2RDunU

As the articles indicate–and again, this is not to say issues do not exist– the problem is far more complex than what you seem to be indicating here on your blog. Now, I have no problems with the second and third points you make, namely:

“that boys’ behavioral problems can at times be the result and symptoms of prior academic problems, rather than the other way around”

and:

“that the rules in lower education are created and enforced fairly and equitably.”

Regarding the first point, that was not an assumption of mine, but, it is far more complex than what is being led on here. There is quite a bit of research that suggests that (and for lack of a widely used term, I’ll say ‘boy behaviors’) “boy behaviors” are routinely targeted and heavily scrutinized in school. This point, which I stated in the interview but it didn’t make it out as clear, can help explain why boys feel uncomfortable, targeted, and may eventually leave school because of such hostile school cultures. And finally, to your third point, anyone familiar with my research could not possibly take away that I felt school rules are enforced fairly and equitably. In fact, I argue just opposite in most of my published research! More specifically, I demonstrate that the rules are unfairly and deleteriously applied to some groups, in particularly Black and Latino *males.* And that this deeply negatively impacts their school success.

Finally, the graphs you referenced, which may indeed seem problematic, is, one, referring to higher education and not K-12, which was what the interview was primarily about, and two, could be more useful if it was pulled out by subject area. It is a problem that men are not entering some fields–I agree! But there is no doubt at all that men still predominate some of the highest paying professional fields, top management positions, and that equally-qualified women make a portion of what men make. That is one of the major points I hoped to convey in the interview. More broadly speaking, it would really help you to reference some of the scholarly literature about oppression and marginalization in school and society, and that would only help you more cogently make many of the points you hope to make. But it would also help you better understand the plight of women a bit better. So to sum it all up, while I agree there are some issues with boys in school, it is not nearly as one-sided and dire as you seem to be suggesting.

Nonetheless, I am glad we had a chance for this exchange, and I encourage more exchanges like this. For any readers wanting more comprehensive research on the gender gap, feel free to email me and I will send along whatever I can. Best wishes!

-Dr. Muhammad Khalifa

Thank you for your comment. Dr. Khalifa. I have just sent an email to you, as follows:

“Greetings. My name is Jonathan Taylor. I’m the founder and primary writer of the website A Voice for Male Students.

I wrote an article on November 13, 2013 concerning some statements NBC affiliate WILX10 reported you had made regarding men and boys in education. Roughly a month and a half later (during Christmas) you responded with a comment on my article, agreeing and disagreeing in part. Part of your disagreement was that either WILX10 or I had misinterpreted your statements regarding equitable discipline procedures in lower education and the school-to-prison pipeline.

You offered to send me some of your scholarly writing to support your disagreement. I would still like to see it, if you have occasion to send it to me. After reviewing some of your work elsewhere, however, I found that either the news station reported your position inaccurately or vaguely, or I misinterpreted it.

To remedy this I have removed the portions of the article relevant to the school to prison pipeline. I have also softened the tone of the article somewhat in various places. The rest of the article remains as it was.”

I understand your views on oppression and marginalization. I understand the Feminist worldview – and your worldview – that women are marginalized from the topmost positions in society, where men are overrepresented.

Where I disagree with you, and with many Feminists, is that I and my fellow men’s advocates also acknowledge that men are overrepresented at the bottom of society as well. Hence, any holistic and truly representative view of education in the context of economic opportunity and gender equity must reflect how men are represented at both extremes.